Előd Pál Csirmaz

The Tomb of the Author in Robert Browning’s Dramatic Monologues

MA Thesis (for MA in English Language and Literature)

Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, Hungary, 2006

Supervisor: Péter Dávidházi, Habil. Docent, DSc.

Abstract

Even after the death of the Author, its remains, its tomb appears to mark a text it created. Various readings and my analyses of Robert Browning’s six dramatic monologues, My Last Duchess, The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church, Andrea del Sarto, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” Caliban upon Setebos and Rabbi Ben Ezra, suggest that it is not only possible to trace Authorial presence in dramatic monologues, where the Author is generally supposed to be hidden behind a mask, but often it even appears to be inevitable to consider an Authorial entity. This, while problematizes traditional anti-authorial arguments, does not entail the dreaded consequences of introducing an Author, as various functions of the Author and various Author-related entities are considered in isolation. This way, the domain of metanarrative-like Authorial control can be limited and the Author is turned from a threat into a useful tool in analyses.

My readings are done with the help of notions and suggestions derived from two frameworks I introduce in the course of the argument. They not only help in tracing and investigating the Author and related entities, like the Inscriber or the Speaker, but they also provide an alternative description of the genre of the dramatic monologue.

2.1 A History of the Death of the Author

2.2 From the Methodological to the Ontological and Back: The Functions of the Author and its Death

B. The Death of the Author as a Technique of Writing

C. The Methodological Death of the Author

2.4 A Theory of Embedded Communicative Schemes

2.5 A Representational Framework

3 The Practice of the Dramatic Monologue

A. Defining the Dramatic Monologue

B. The Paradoxes of Robert Langbaum

C. The Reception of the Dramatic Monologue

B.1 My Last Duchess and Browning’s Audience

3.4 The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church

B.1 Reception in Browning’s Time

B.2 Reading Readings of Later Days

3.6 “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”

B.1 Assessments of the Contemporary Audience

It has been a critical commonplace for a long time to suggest that the Author is dead, that it died a common death with Man, or that it is continually sacrificed in the process of writing. Lately, it has also become common to suggest that despite its discontinued existence, the Author has the capability to return, based on Seán Burke’s treatise, its primary aim being to deconstruct texts announcing its death.

In this work I undertake the task of investigating to what extent and in what ways the Author can be considered present or absent in a class of poems in which the position of the Author is widely considered to be exceptional: exceptionally absent in the seeming dominance of the Speaker of a dramatic monologue, exceptionally hidden behind the Speaker–mask prohibiting the Readers from guessing Authorial judgment on the Speaker, or even exceptionally present in the gap opened between the expressed intent of the Speaker and its textual performance bordering on an unintentional confession. In other words, I consider what remains of an Author after its alleged death, figuratively speaking, how its tomb marks a text it authored. I concentrate on Robert Browning’s oeuvre in order to ease the task of considering the biographical Author in my analyses, and also as, in my view, Browning’s oeuvre, historically, is situated in a period that could be regarded as transitional between the Romantic (in Robert Langbaum’s sense) and the modern, in ways anticipating even the postmodern technique of dislocating and relativising a central, an Authorial voice. My aim was to provide readings of poems that span as many possible set-ups according to as many characteristics as possible, while limiting the number of dramatic monologues analysed in order to be able to give a detailed analysis of each. I have selected Browning’s My Last Duchess, The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church, Andrea del Sarto, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” Caliban upon Setebos and Rabbi Ben Ezra. Apart from my readings of these poems, other reviews, contemporary or later ones, shall also be considered to determine Authorial presence as felt by other readers.

In the first part of the thesis, I provide an overview of anti-authorial arguments and their critiques, and introduce some basic concepts with which the presence and functions of Author-related entities will be examined during my readings. I start the second part with a brief consideration of theories regarding dramatic monologues in general, and continue with the readings of the poems treated separately, one by one. Alongside my investigation of the Author, I also test a closely related suggestion regarding an internal structural characteristic supposedly true of dramatic monologues in general.

“Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice;

Take each man’s censure, but reserve thy judgment.”

Shakespeare

Polonius

Poster scribbled over in a classroom of the School of English

and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University

2.1 A History of the Death of the Author

In M. H. Abrams’ classification of eras of criticism, found both in The Mirror and the Lamp and in “Orientation of Critical Theories,” the Author as the main point of reference seems to have been born at the point of transition from mimetic and pragmatic critical theories to expressive ones:

But once the theory emerged that poetry is primarily the expression of feeling and a state of mind […] a natural corollary was to approach a poem as a revelation of what Carlyle called the ‘individual specialties’ of the author himself. […] For good or ill, the widespread use of literature as an index—as the most reliable index—to personality was a product of the characteristic aesthetic orientation of the early nineteenth century. (“Literature as a revelation of personality” 18–19)

The death of the Author, according to the lineage presented by Roland Barthes in “The Death of the Author,” started with Mallarmé, continued with Valéry, Proust and the Surrealists (168–169).

The closeness of the dates of the birth and the death of the Author presented by these sources (Mallarmé was born in 1842 and died in 1898) shows the problematic nature of fixing the times of or attributing to movements or changes in metanarrative-like orientations the birth and the death of the Author. The above presented trials to do so inevitable exclude other uses and functions of the Author as, for example, unificator of discourses; moreover, what they entail, namely, that the Author came into existence at a specific point in time and (will) cease(d) to exist at another, echoes the notion of the modern episteme by Michael Foucault in The Order of Things, which episteme is the only home of the subject, of man, and of the Author, and with its end (will) disappear(ed) all three of these entities (Burke 62–115).

Seán Burke, in fact, criticises vehemently the lineage presented by Barthes. In The Death and Return of the Author, in which he undertakes the task to deconstruct anti-authorial texts mainly by Barthes, Foucault and Derrida (the modern edition of Blake’s unholy trinity as far as the godlike transcendental author is concerned), he lists Mallarmé and T. S. Eliot, descriptors of a “certain compositional mood whereby the poet attempts to empty himself of personal concerns” (10); the Russian Formalists, Czech and French structuralists, Ferdinand de Saussure, Lévi-Strauss and Jacques Lacan, whose work centred around the establishment of a structural science of language, literature and the psyche (10–12); and finally, New Criticism and again the Russian Formalism as movements against biographical positivism in criticism (14) as precursors to the death of the Author announced by Barthes in the poststructuralist ‘era.’ As a further example, one might also add Mark Schorer to the group of T. S. Eliot, as he likewise called for the separation of the personal from the work of art via technique.

Burke deconstructs Barthes’s texts mainly on the basis that he allows the author to return while, at the same time, tries to uphold the idea of its death (a notion also subverted by Barthes’s concentration on the oeuvre in Sade Fourier Loyola and his notion of ‘founder of language’) (Burke ch. 1). Burke does the same with Foucault’s notion of the epistemi, which are absolutely discontinuous and have total control over discourse in a given era, on the basis that the argument in The Order of Things exalts Nietzsche to a supra-epistemi level as he is able to talk “out of” the present episteme and about the coming one. Burke also sees the notion ‘founder of discursivity’ introduced in “What is an Author?”, rightfully, subverting the very notion of epistemi, whose ability to control discourse would render authors passive and insignificant. The status of the text of The Order of Things is also considered, which, speaking “about” and not “for” the modern episteme, cannot possibly belong to it. Seemingly, Foucault has referred to Nietzsche in order to distract attention from the supra-epistemi location of his own text and himself. (Burke ch. 2) Burke sees the same problems emerging with Lacan’s anti-subjectivist texts. Here not epistemi, but a linguistic unconscious controls all utterance and text, still, Lacan appears to suggest that he “speak[s] of rather than in a language prerequisite to any subject” (Burke 101), therefore rendering his treatise self-contradictory.

Of Grammatology by Derrida, in Burke’s view, repeats the pattern of The Order of Things inasmuch as while it denies the importance and even the existence of authorial subjects, it gives Rousseau a privileged place and even cites biographical evidence in the readings of Rousseau’s texts. In fact, Burke suggests that later on, Derrida attempted to modify his anti-subjectivist standpoint, and arrives at the conclusion that the very notion of deconstruction renders the author and authorial intention, which is to be reconstructed from a text in order to be deconstructed, important and existent, if not straightforwardly central. (ch. 3)

From this brief overview of a criticism of anti-subjectivist and anti-authorial texts it is apparent that one of the central problems emerges when a text (or, better to say, theory) postulates that not the Author but something else (epistemi, language, etc.) controls discourse, as this set-up immediately rules out the existence of a text that appears to situate itself outside the constraining forces. Also, the fundamental difference between a transcendental author and a supradiscourse constraint remains unclear, as is the reason why a preference for the latter is better.

Most of the analysed texts, and specifically, Burke’s arguments, however, appear to say little of texts which do not address the question of the placement of the Author directly, and specifically, of literary texts of that kind, as these texts do not entail the contradiction between their arguments and their situatedness which Burke’s deconstructions are mostly based on. In order to extract from anti-authorial texts statements, theories or fragments of theories that could be more or less directly used to address the question of the presence of the Author in literary texts, I propose a series of notions of the Author around which theories of its death may be grouped.

2.2 From the Methodological to the Ontological and Back: The Functions of the Author and its Death

The fact that the Author and its death can be interpreted and viewed in several, often contradictory, ways is also emphasized by Burke, who distinguishes between two levels: the methodological, in which the death of the Author is an optional basis of critical approaches to literary texts, and the more transcendental notion of the death of the Author as a prerequisite and axiom of all discourse. He attributes many of the inherent contradictions in the analysed texts to the non-segregation of these two meanings: “Much confusion, in fact, arises from the neglect of this distinction, from confounding the death of the author as a speculative experimental approach to discourse with authorial absence as the truth of writing itself” (175). Based on the texts he analysed and other treatises on the death of the Author, however, more centres of the various meanings of ‘Author’ and the ‘death of the Author’ can be established, which could also be called the functions of the Author in (literary) discourse. I have managed to establish the following four categories of ‘meanings’: the extratextual / biographical author, the death of the Author as a technique of writing, the methodological death of the Author, and finally, the transcendental Author. Sometimes these categories are based on oppositions; at other times, they can be seen overlapping. The importance of the proposed separation of the functions of the Author is that later, the investigation of the presence and/or fulfilment of these functions can be narrowed down in my analyses of Browning’s dramatic monologues. The listing of these functions will also serve as a backbone to my review of texts read by Burke and of other essays on the death of the Author not treated in his book.

I grouped together meanings of the Author under this heading which refer to the material, biographical entity. As such, it is necessarily extratextual and often regarded as existing prior to the text.

One of the essays in which the usage of the ‘Author’ is dominantly in this sense, is Russell A. Potter’s “Authorship.” Dealing with the effects of the dawn of the Internet, the World Wide Web and instant publication on the notion of the Author, he treats copyright, legal and financial issues at length. Citing the New Critics and Foucault, and then arguing against them that “despite all these multiple notices and certificates of death, however, the ‘Author’ has continued a lively postmortem existence” (148–149), he writes:

As the name of the Critic supplants that of the Author, the weary student may be forgiven for thinking that this brave new critical world bears an uncanny resemblance to the old world of ‘Authors’ and their affects that those critics worked so diligently to defuse.

One of the reasons that this is so, curiously enough, is that the very media which were supposed to disperse and alienate the affective ‘aura’ of the author have instead resuscitated the power of authorial presence. We are never so easily persuaded of authors’ dramatis personae as when we see them interviewed on television, banter with them in an on-line chat, or listen while driving to their voice reading from a cassette tape. (149, emphasis added)

This argument against the death of the Author is clearly based upon its biographical function. It is worth noting that the movement of New Criticism argues against recurring to the Author in criticism, that is, on a methodological level (see, for example, Burke 138–139). The functions of the Author listed by Foucault in “What is an Author?” are extremely complex, but, at the first level of approximation, they can be regarded as connecting a transcendental Author to discourses, either unifying texts in oeuvres or unifying writer and narrator. Arguing against these postulates on the basis of a biographical view shows how easily the categories or levels of functions are mixed up, rendering the validity of a whole argument questionable.

This is not to say that there are no connections or overlaps whatsoever between the categories I am presenting. The extratextual, biographical Author is connected to its ‘methodological death’ in criticism and reading if, for example, authorial intention to be avoided is not reconstructed from the text but from, to borrow Barthes’s term, biographemes. It is connected to its death as a prescriptive requirement for writing in the case of T. S. Eliot, for instance, who argues that emotions / feelings of the living author should not find their way directly to the writing (“Tradition and the Individual Talent” passim). But the material, biographical author is in most cases in opposition to the transcendental one, the two which Potter’s essay seeks to bring together and apparently equates.

It is because of the strong connections mentioned above that I shall discuss other arguments also making use of the biographical / extratextual function of the author in the following sections, as I think their main focus is on other ‘meanings’ of the ‘Author.’ However, to illustrate that treating this function is by no means restricted to Potter’s essay, one could cite The Pleasure of the Text by Barthes: “As institution, the author is dead: his civic status, his biographical person have disappeared” (qtd. in Burke 29, emphasis added). Barthes also appears to argue against the biographic view of the Author when he, arguably, separates the pre-textual Author and the Scriptor “born simultaneously with the text” (“The Death of the Author” 170).

B. The Death of the Author as a Technique of Writing

The earliest proclamations of the death of the Author appear to describe a technique to be followed by writers who wish to produce anything that is worth of interest. T. S. Eliot, in “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” does this in two senses: first, by encouraging tradition and a network of literary works (a discourse), in which “no poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone” (72), and in “what happens is a continual surrender of himself as he is at the moment to something which is more valuable. The progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality” (73); and second, by suggesting that an artist should separate in herself the sufferer / experiencer entity and the creative one (74–76). Eliot connects these two theses in his likening the artist to a catalyst, which renders him similar to the passive authors in Foucault’s epistemi.

Somewhat later, Mark Schorer sounded similar prescriptive requirements. In “Technique as Discovery,” he regards technique, that is, the mode by which one treats the experience to write from, a necessary step in creating valuable novels. Based on the analyses Schorer provides, it appears that a technique is deemed appropriate if it separates the experience from the author. He repeats twice: “Technique objectifies” (7, 9). In the absence of such technique and separation, the work of art is not as good as it could be. “The point of view of Moll is indistinguishable from the point of view of her creator [Defoe]” (6), “Lawrence [in his Sons and Lovers] is merely repeating his emotions, and he avoids austerer technical scrutiny” (13) he complains, and concludes that this way, the novels became uninterpretable and, ultimately, turned upon themselves and destroyed any ‘meaning’ they could momentarily present and preserve. The separation, or mastering of the original experience echoes the requirements made by T. S. Eliot, and, if one may put it this way, calls for the death of the writer (not necessarily the extratextual Author only) in, or before the writing s/he creates.

Notably, a similar requirement may be argued to have surfaced much earlier. The famous phrases from Wordsworth’s “Preface to Lyrical Ballads, with Pastoral and Other Poems,” similarly to the above two essays, appear to argue for the careful evaluation of an experience before it is used as material for writing:

For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: but though this be true, poems to which any value can be attached, were never produced […] but by a man who […] had also thought long and deeply. (2:242)

It [poetry] takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity (2:250)

Both of these excerpts contrast feeling or emotion to a contemplative phase (thinking, recollection) in which it is transformed and made fit for poetry. In this respect, the above definitions of poetry closely echo Schorer’s notion of technique there applied to prose. Pushing them to the extreme, they again require the sacrifice (death) of the original experiencer before writing begins.

Let me point out that many of the above arguments could be regarded as using the notion of the ‘Author’ in the biographical sense discussed in the previous section, as they are calling for the exclusion of the original experiencer or sufferer from literary works. However, the fact that whether this exclusion took place or not is often determined based on the produced text (most notably in Schorer’s case), therefore, what has to be dealt with is not only a biographical, but also an intratextual Author reconstructed from the very text s/he is supposed to be separate from. This is also why I have grouped these arguments in a separate category.

C. The Methodological Death of the Author

In this diverse category, I have collected arguments which call for the death of the Author from the point of view of reading / criticism, or regard the Author as a result of the act of reading, that is, as an a posteriori intratextual[1] entity.

T. S. Eliot’s article may again be cited as referring to this ‘meaning’ of the Author. When he argues for an “impersonal theory of poetry” (74) suggesting that criticism should be directed at texts rather than their authors, he, it can be suggested, argues for the exclusion of the author as a method to approach literary texts.

Barthes in “The Death of the Author” also approaches the death of the Author from a methodological point of view. He criticises the current method of critics to discover the Author “(or its hypostases: society, history, psyché, liberty)” in a work of art, thus closing its interpretative field and explain it away (171).

Foucault also makes similar suggestions. In “What is an Author?”, when he describes how work has taken the place of the missing Author, the death of the Author in criticism is already set in the past: “It has been understood that the task of criticism is not to reestablish the ties between an author and his work or to reconstitute an author’s thought and experience through his works” (140). This presentation of the death of the Author is also from a methodological point of view.

Criticism or reading based on the ‘Author’ immediately leads to an important problem: that of the treatment of Authorial intention. Burke treats this issue at length (138–149). He cites various approaches to intention: the school of New Criticism, which attempts to do away with it as it is irrelevant and cannot be reconstructed; the movement of New Pragmatism which postulates that authorial intention is equal to textual performance, and finally, Derrida and deconstruction, who (which) regard authorial intention as capable of controlling portions of the text, but not its totality, thus textual meaning is different from and can be contrasted to a reconstructed authorial intention to deconstruct it. The suggestion that Derrida and deconstruction appears to make an often intratextual, reconstructed author central becomes especially important if contrasted to other suggestions of Derrida on the nature of subjects and authors, to be discussed in the next section.

Foucault’s essay could be cited on one more instance in this section, as it appears to suggest that the “author–function” is constructed by the consumers of discourse:

The third point concerning this “author–function” is that it is not formed spontaneously through the simple attribution of a discourse to an individual. It results from a complex operation whose purpose is to construct the rational entity we call an author. (143)

This notion of the Author is undoubtedly a posteriori, and, as it appears to be derived from discourse, in a sense, intratextual. Foucault repeats the positioning of the Author in the Readers: “these aspects of an individual, which we designate as an author […] are projections, in terms always more or less psychological, of our way of handling texts” (143). This situating of the Author, similarly to the case of Derrida, can and shall be contrasted to a more transcendental or rational view on it also expressed in the same essay.

In the last category I have grouped uses of the notion of the ‘Author’ which see it as transcendental, a subject whose ontological status reaches beyond materiality; which see it, if determined, as a guarantee of textual meaning, regardless whether it is based on a biographical entity or not; and finally, which see it as an entity whose death is an inherent property of writing and discourse.

That Barthes, in “The Death of the Author,” (also) refers to a transcendental Author which is to be done away with, is straightforward, as it is equated with the / a “final signified” and coordinated with society, history, psyché, liberty; God, reason, science and law (171). Moreover, its death characterises all writing: “Writing is [the] space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing. // No doubt it has always been that way” (168).

Arguing on the basis of the postulate of metaphysics as an “all-inclusive episteme” (Burke 120), Derrida, presenting all texts as regulated by this metadiscourse, appears to suggest in On Grammatology that writing subjects are either lost or irrelevant. “The names of authors or doctrines have here no substantial value. They indicate neither identities nor causes” (qtd. in Burke 121); “there is not, strictly speaking, a text whose author or subject is Jean-Jacques Rousseau” (qtd. in Burke 120). Thus, it could be argued, Derrida makes the loss (death) of the Author an inherent property of writings regulated by this episteme.

Foucault’s “What is an Author?” recurs to an Author which can be seen transcendental in a different sense. When he suggests that the Author is a function of discourse which regulates its “existence, circulation and operation” within a society (142), or when he situates the Author as the unifier of and mediator between writer and narrator: “the ‘author–function’ arises out of their scission—in the division and the distance of the two” (144), reference cannot be made to a material entity. Instead, the author–function can be seen emerging as a necessity, as a requirement of discourse in both cases. Here, it is not the death of, but the Author(–function) itself that is seen as a property of discourse in general, thus lifting it above the material level to the hypothetic, logical, in a certain sense, transcendental one.

From this brief list of arguments about the functions of the Author it is clear that many texts on which the notion and the tradition of the death of the Author rests overlook the distinction between the various functions or instances of the Author, the distinctions between a priori and a posteriori, extratextual and intratextual, material and transcendental Authors. (Burke also calls attention to this fact, although he traces this absence of distinction between two levels only, the methodological and ontological. Also, the examples he gives are not from within one text; he contrasts fragments from different works of the same author. [175]) Not only Potter argues against the death of the transcendental Author on the basis of the continued existence of the biographical one; it is not only Eliot who regards the death of the Author as a method of writing and as a method of criticism, arguing for, on the one hand, the death of the biographical, on the other, that of the reconstructed Author; but Barthes’s essay can also be seen as cutting in every direction: proclaims the death of the extratextual Author, leads critics out of the darkness of the search for a reconstructed one, while regarding the Author transcendental at the same time.

Foucault’s views on the author–function, as a result of psychological operations and something that appears to be a property of discourse, seem to be reconcilable, as these two views reflect, for example, the position of language which can be seen as the product of subjects one the one hand and as an objectively existing system prior to them on the other. However, Foucault still appears to accept, without question, the “empty slogans” now not untrue, merely insufficient, that “the author has disappeared; God and man died a common death” (141), which entail an Author transcendental prior to its death, a view hardly reconcilable with any of the positions on the author–function he takes.

Derrida, based on Burke’s reading, can be similarly seen as blending Authors—the methodological one postulated by deconstruction and the transcendental one based on the antisubjectivist nature of metaphysics.

In order to avoid the blurring of the distinctions between the various functions of the Author, or Author–functions, which, as could be seen, can seriously undermine the validity of arguments, I shall follow these two stratagems in my analyses of dramatic monologues: first, I shall narrow the scope of functions to be analysed, and shall primarily concentrate on the presence, the absence and the role of the extratextual / biographical Author—regarding the arguments calling for the necessary death of the Author as a technique of writing as referring to the biographical writer—and on those of the Author (re)constructed in the act of reading. I shall deal with the transcendental function of the Author only as a function of discourse.

Second, I shall attempt to break down the Author into a series of entities, assigning one function to each. This way, a clear distinction between the functions can be easily upheld.

An attempt to separate author-related entities is not new. Let me therefore, before investigating the consequences of such a division and the properties of the resulting entities, briefly review some texts containing examples of such a separation.

Barthes, in “The Death of the Author,” might be contrasting Author and scriptor when he writes: “The Author is thought to nourish the book, which is to say that he exists before it […] the modern scriptor is born simultaneously with the text” (170) provided that he uses scriptor not merely as a synonym of Author and writer. The unintentionality of the Author–Scriptor opposition in Barthes’s text is supported by the fact that despite the dual opposition he sets up, “Author”, “Author–God”, “writer” and “scriptor” can all be found in the text (in its English translation), and it is often unclear whether there is any difference between Author and Author–God and to which side of the duality writer would refer to. However, that Barthes intentionally contrasted scriptor to Author is supported by his suggestion that “[s]ucceeding the Author, the scriptor no longer bears within him passions, humours, feelings, impressions” (170). In conclusion, Barthes’s essay can be argued to propose a distinction between a pre- and extratextual and a post- and intratextual Author.

Foucault’s “What is an Author?” appears to refer to the very same two entities in a passage partly quoted already:

It would be as false to seek the author in relation to the actual writer as to the fictional narrator; the “author–function” arises out of their scission—in the division and distance of the two. (144, emphasis added)

Here, the Author appears not to be identified as the extratextual, biographical entity (the actual writer)—as it happens, despite the usage of the word writer, in Barthes’s essay—but the three entities are situated in an interesting triangle, the ‘author–function’ being, or becoming, or being constituted by, in a sense, both of the others. Still, at the base of this arrangement the same duality appears which Barthes describes.

To complicate matters further regarding this—let me add, quite natural and widespread—dual view on the Author, one could cite Geoffrey Nowell-Smith’s essay titled “Six Authors in Pursuit of The Searchers” in which he problematizes this set-up. Criticising the idea that the author is naturalised as a sub-code of a text, that is, “the author (external to the text) records his presence through the signs of [a] sub-code,” he claims that “the author as effect of the text cannot simply be objectified in the form of a sub-code. Nor can this supposed sub-code be then re-related, tel quel, to the author as producing subject” (222). His argument for these theses is that the authorial sub-code cannot be put alongside with non-authorial ones. He sees the Author as surfacing on various levels the ‘text,’ and based on this observation he proposes either to postulate the existence of many authorial sub-codes or to regard the Author as a system (223).

In fact, a system-like longer series of entities appear in the series of essays by Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida and Barbara Johnson progenerated by Edgar Allan Poe’s The Purloined Letter. Lacan, in his “Seminar on ‘The Purloined Letter’,” in fact, considered only the series of characters through which the two purloinings are related; he talks about the “double and even triple subjective filter” (34). Derrida, in turn, in the “Purveyor of Truth,” accuses Lacan of not recognizing layers above the narrating characters:

But what the Seminar treats is only the content of this story […] Not the narration itself. […] One might be led to believe, at a given moment, that Lacan is preparing to take into account the (narrating) narration […] But once it is glimpsed, the analytic deciphering excludes this place, neutralizes it [which] transforms the entire Seminar into an analysis fascinated by content. (179)

Derrida postulates the existence of a further layer, in his term, frame, that of fiction, which is generated by the inscriber, and states: “Lacan excludes the textual fiction from within which he has extracted the so-called general narration” (180). He lists the narrating narrator, the narrated narrator, the author and the inscriber as entities authoring various frames of Poe’s ( ? ) text (179).

Johnson, in her “The Frame of Reference: Poe, Lacan, Derrida,” reads Derrida’s reading as, at first sight, one that argues for identifying literary language with a framed one: “Lacan, says Derrida, misses the specifically literary dimension of Poe’s text by treating it as a ‘real drama’ ” (127). She quotes Stanley E. Fish concluding, in a similar manner, that “literature is language… but it is a language around which we have drawn a frame” (qtd. in Johnson 128). However, in her reading, Derrida also appears to subvert the logic of the frame, claiming that while it is obligatory to draw a frame around a text, it is, at the same time, impossible to do so. Johnson suggests that Derrida in this way sought to challenge the limits of the spatial logic of frames (128–129).

One is still left with an abundance of entities related to or situated in, below or around the Author whose functions and qualities are defined in often contradictory ways. As an attempt to unify these entities with narrating characters in narrations (as Lacan brings Poe and the characters to the same level), I shall propose a model in which many of these entities can be situated. Based on this model, the definition of literariness by frames can be connected to other arguments on what property constitutes an artistic text. Being a simple and abstract model, it, however, will not venture into explaining how the enclosed text deconstructs the frames around it; it remains in a pre-poststructural world of thought.

2.4 A Theory of Embedded Communicative Schemes[2]

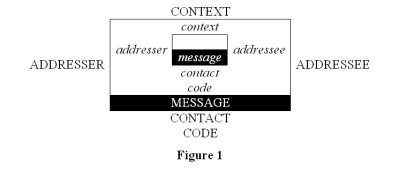

The model of messages or narrations retransmitted or re-quoted via a series of Author-related entities or narrating characters is based on the model of communication presented in Roman Jakobson’s essay titled “Linguistics and Poetics.”[3] This model contains six elements or factors: the (textual) message is coded and sent by the addresser; it is received and decoded by the addressee. The message is provided with a context it may refer to; a contact (a channel) is established between the addresser and addressee which makes the transmission of the message possible, and finally, a common code (language) is shared by the two parties which renders the message intelligible for the decoder. (Jakobson 35)

Six functions of language are paired to these six elements, depending on which element in the model appears to be the most salient in the message. A referential message is primarily denotative and focuses on the context. An emotive one reflects (expresses) the addresser’s attitude; if the message is oriented toward the addressee, it is conative. To these three functions are added the phatic function, which focuses on maintaining and enhancing the contact, and the metalingual, which focuses on the code, when clearing up, for example, misunderstandings based on an unknown word or phrase. The final function, when the message is oriented on itself, is the poetic one. However, Jakobson is quick to point out that “[a]ny attempt to reduce the sphere of poetic function to poetry or to confine poetry to poetic function would be a delusive oversimplification. Poetic function is not the sole function of verbal art but only its dominant, determining function” (37). As it will be apparent from the proposed model, self-focus, although in a slightly different sense, can indeed be connected to a hypothetical literariness of a text.

The model of retransmitted messages builds on the multiplication of the above described model of communication by inscribing all six factors of a quoted message (communication) in the message of the superordinate communication. In the ensuing argument, let me focus on the topmost two levels of this retransmission, as it is on the upper levels that author-related entities that might be overlooked are situated. Addressers on lower levels (characters), the communicative schemes of which are not embedded in each other, but are coordinated, are easily recognised as distinct. See Figure 1 for a representation of two layers of communication. In accordance with the notation used in the illustration, factors and functions in uppercase refer to those of the outer, while those in lowercase italic letters refer to those of the embedded communication. Thus ADDRESSER, the most general one, is the extratextual Author; the ADDRESSEE the extratextual Reader. MESSAGE, expectedly, is the literary work itself. CODE, CONTACT and CONTEXT can be established based on the circumstances of the writing and the reading of a work: whether they happen simultaneously, or in a deferred way; what language is used, and in what cultural, social and historical the work was (is) written and is read. Let me now turn to the functions of the embedded communication.

The addresser can be regarded to be the intratextual Author, as it is generated solely by the work, the MESSAGE. Following Lacan’s reading of Poe’s story, it can be postulated that it is the Narrator, and the message is the narration, as opposed to the whole work, the MESSAGE. If, following Derrida’s framing, the presence of a further frame (that of fiction, whose addresser is the Inscriber) is to be accounted for, the model should include not one, but two embedded communications, one embedded in the other. If the inquiry is continued maintaining the dual model, that is, that the message is in fact the narration, then the message excludes the title, the occasional sub-title, motto, etc. of a work. As they are included in the MESSAGE, they can be interpreted as enriching the context of the message against which it is interpreted. (An observation of special importance in the analyses of Browning’s poems.)

In the case of the upper levels of this hierarchical model of literary texts, and in cases where characters use direct quotation to retransmit a message, CODE=code can be generally postulated. Leaving the interpretation of the contact aside for the moment, what one is faced with is the question of the addressee, which will, in fact, destroy the symmetry of the model by cutting it in half.

The addressee might be regarded to be the implied reader or the Reader-in-text, who is the formal addressee of the message by the addresser, in reality intended for the Reader (ADDRESSEE). The addressee might be directly pointed at whenever the Author-in-text appears to address her directly, as in, for example, the supposedly conative preface by William Makepeace Thackeray, “Before the Curtain,” to his Vanity Fair. However, such a text might be better regarded to be authored by an addresser situated between the ADDRESSER and the Narrator, as it may even make references to portions of the text traditionally not considered to be included in the narration (chapters, titles, remarks situated outside the time and place of the narration, etc.). In other words, even a direct address appears to fail to assign a place or at least to point to and thus define the intratextual Reader. The addressees of the embedded communications seem even harder to separate than their addressers (extratextual Author, intratextual Narrator, Scriptor, etc.), which suggestion might be explained by the fact that while messages may originate from apparently distinct sources, all of them are addressed to the ADDRESSEE, or, at least, are intended to be overheard by him. (Please note that an addressee might be easily definable on lower levels, where the addressers are characters engaging in dialogues. In these cases, the corresponding addressees, in most cases, are other characters. However, at the present moment, my analysis is restricted to the upper levels of communicative schemes.)

Two arguments present themselves as possible ways of explaining away the situation of embedded addressees. The first solution can be reached via the notion of the representation of the Reader in the literary work. On the one hand, it can be regarded to be the addressee, as this is the entity the narration (fiction) is addressed to. On the other hand, as the narration is presented from the Narrator’s (addresser’s) point of view, and this is the standpoint the Reader perceives elements in the narration from, the Reader also seems to be represented by the addresser.

Please note that the presence of a character in or around the narration who is presented as one listening to the narration, that is, an auditor, does not undermine this argument. Non-silent auditors, like Mr. Gigadibs in Browning’s Bishop Blougram’s Apology (see lines 996–1004), when they speak, simply seize the point of view and become addressers themselves. Throughout silent auditors, like Lucrezia in Andrea del Sarto, seem to merely modify or add to than to define the point of view the Reader is forced into.

It could be argued that this interesting set-up of representations merge the addresser and the addressee in the reception of a literary work. Thus, addressee can now be situated: it is equated to the addresser.

It is worth noting that theories and movements related to the methodological death of the Author, in many instances, appear to call for a view on literary texts where not only its Author is dead, but it is also stripped of the historical context of its composition, and, in some cases, the context of its reading: it is attempted to analyse the text as it is. In other words, the MESSAGE is stripped of its CONTEXT, ADDRESSER and ADDRESSEE. In this framework, it then comes as no surprise that the agents of the message, the addresser and the addressee, having no available antecedents, are turned on and are identified with each other.

The behaviour of the MESSAGE in this, reduced environment, is also predictable: it becomes self-reflexive, that is, POETIC; and it was the prominence of this function which Jakobson argued to mainly coincide with literariness (37).

The second argument, based on the suggestion that all messages are addressed to the Reader, postulates that there are no embedded addressees at all. The reason why the problem to find a suitable interpretation for the Reader-in-text-s—the existence of which is postulated solely on the basis of the model of communication—is so problematic to settle is that these entities can be easily regarded nonexistent. This entails that embedded communications are reduced versions of communicational schemes pretending to be full embedded ones. In other words, they are not independently interpretable, and they do not retransmit or re-quote messages originating from lower levels in the proper sense of the verbs. All messages originate from the ADDRESSER, the extratextual author, and reach the Reader via one of the mask-like embedded addressers.

If so, the messages are not distorted fundamentally by the nonprocess of not re-quoting them. This fact is what makes it possible for readers to merge the Author with the Narrator so easily. It cannot be resisted to quote Lacan doing so in his “Seminar”: referring to Dupin’s remarks on the meaning of certain Latin words, he remarks: “No doubt Poe is having a good time” (37, emphasis added); criticising Dupin’s treatment of mathematicians, he refers to “Poe’s experience” (38).

In fact, the conclusion that embedded communications are reduced can also be reached from my first argument. Both arguments render the embedded addressees rudimentary: the first by equating them with the addresser, the second by suggesting that they are nonexistent.

Furthermore, the notion of reduced communicative schemes echoes Jakobson’s quasi-quotation. However, the following excerpt makes it apparent that he regards all factors of all implied communications distinct and existent, whereas I argue for their reduced nature as far as the upper levels of embedded communications are concerned. His term ‘simultaneously’ is also made more concrete as the embeddedness of communicative schemes in my model. Jakobson writes:

For instance the poem ‘Wrestling Jacob’ is addressed by its title hero to the Saviour and simultaneously acts as a subjective message of the poet Charles Wesley to his readers. Virtually any poetic message is a quasi-quoted discourse with all those peculiar, intricate problems which ‘speech within speech’ offers to the linguist.

The supremacy of poetic function over referential function does not obliterate the reference but makes it ambiguous. The double-sensed message finds correspondence in a split addresser, in a split addressee, and besides in a split reference. (50)

Foucault also uses the term “quasi-discourse” in reference to literary texts, to novels and poetry, in which one finds a “plurality of egos” (144).

Literariness is also related to quotedness in Brett Bourbon’s Finding a Replacement for the Soul, Mind and Meaning in Literature and Philosophy, chapter 2, “The Logical Form of Fiction.” Investigating the ontological status of objects in fictions and the truth-value of fictional assertions, Bourbon suggests that fictional statements are not meant, but are not lies, either. He sees a way out by suggesting that fictions are quoted (51, 58, 75). He also connects this suggestion to the assertion that a quoted utterance lacks a speaker (59, 76). While the first suggestion is in line with my argumentation on viewing literary discourse as a hierarchy of embedded communications, the relationship between the second, quite Barthesian statement and my position is twofold. On the first level of approximation, I postulated the existence of all factors for all communicative schemes, including the addressers of embedded, quoted ones. This is clearly in opposition with Bourbon’s suggestion. Together with the reduction of the addressees, however, the status of embedded addressers was also problematized. In this sense, the two standpoints can be seen as converging.

Bourbon also considers what constitutes fictionality. He arrives at the conclusion that fictional-ness is situated outside the logical form of sentences. In his view, the Reader perceives a text as fiction because he is sent a signal outside the text that it is to be taken fictionally (62–68). However, Bourbon is quick to add that “whatever conventions we take as signalling that something is fictional (not real) they cannot constitute the fictionality of the story” (65). Having made little references to the nature of such signals, one may connect the notion of fictionality (literariness)-signals to Foucault’s view on the author–function determining the functionality of discourses in societies. (Names of) Authors may well serve as signals as to how their texts are to be read.

This model, in other words, connects literariness defined as framedness by Derrida, as qoutedness by Bourbon and Jakobson, and as poeticness by Jakobson. Its importance for the analyses of Browning’s poems lies in the fact that it helps to explain how the Author, the Speaker / Narrator and other embedded addressers co-exist in dramatic monologues. It provides a background against which the fact that the outer form (rhyme and rhythm patterns) and the language of dramatic monologues are almost always exclusively controlled by the Author can be explained, and the hierarchy it postulates explicates why speakers quoted by the Speaker in dramatic monologues also conform to these formal constraints (consider, for example, Agnolo’s words quoted by Andrea in Andrea del Sarto [ll. 189–193].) The postulate of the reduced nature of embedded communicative schemes may also throw light on the question why Speaker and Author, as I shall attempt to show, are often attempted to equate even in dramatic monologues. And finally, it is on the basis of the segregation of MESSAGE and message that I regard texts surrounding the narration (the monologue proper in dramatic monologues) as not originating from the Speaker, but from an entity above, in most cases, from the Author. Based on the suggestions of this model and on the closereading of such portions of the poems (generally, the title and the subtitle) it can be suggested that the presence of the supposedly dead Author can still be felt in these passages.

2.5 A Representational Framework

I have suggested that I shall primarily focus on the biographical and the constructed Author in my analyses. Let me therefore further elaborate the notion from the previous section that the agents of the MESSAGE are represented in a text by the agents of the embedded message. Specifically, I shall postulate that the extratextual Author (the ADDRESSER) gains representation in the form of the (an) intratextual Author or the Narrator (the addresser, or one could even use ‘lyrical I’).[4] Let me consider a few concepts that will have crucial importance when investigating this representational relationship and the ‘internal’ structure of dramatic monologues.

Many of the following concepts and supposed connections are based on Éva Babits’s theoretical collage presented during her lectures at Mihály Fazekas Grammar School, Budapest, 1997–2001. While it became evident to me that her ideas were influenced by a variety of theories, their selection and unification was undoubtedly her own work; a work so thorough and meticulous that it rightly deserves a direct citation. However, I have modified and added to this framework at many points, mainly influenced by my further studies.[5] Especially relevant was John Fizer’s review of the theories of Alexander A. Potebnja, describing Potebnja’s suggestion on the threefold structure of literary works.

Alexander A. Potebnja (1835–1891) was a Ukrainian intellectual. While René Wellek does mention him in his A History of Modern Criticism, and perceives him as one anticipating Croce and Vossler (Fizer v), his theory has remained virtually unknown to the Western world (Fizer 1). This, according to Fizer, is due to the fact that Potebnja himself “did not regard criticism as his main intellectual concern,” focusing, instead, on linguistics. The reception of his work in the Russian Empire was, at the beginning, similarly limited. Later, however, it seems to have raised widespread interest, which was terminated by Socialist Realism in the 1930s (Fizer 1–2). I shall present relevant elements from Potebnja’s theory alongside with the concepts I wish to introduce.

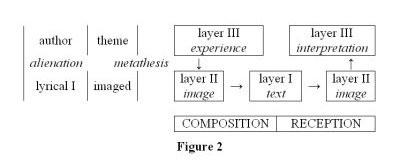

This framework postulates the existence of three layers both in the process of composition and that of reception of a work of art; the processes being regarded symmetric. See Figure 2 for a diagram of the layers, the processes and related concepts.

Layer III is situated outside the work. In the compositional process, it is the original experience, problem, etc. experienced by the Author which becomes represented—according to this model—in the work of art. In reception, layer III is the interpretation of the work by a Reader. Generally, it is supposed that the original experience of the biographical Author is irrecoverable from the text and that interpretation differs among readers. In opposition to the text, which—with a gross oversimplification—can be regarded as existing objectively, layer III is classified, recurring to the subjective–objective dichotomy, as subjective.

Layer I is the textual level. It is the message transmitted, but it can be argued that it also contains connotations, associative elements generally available to members of the interpretative community the artistic discourse is taking place in. (I have disregarded the case of deferred communication, in which the interpretative community in which a work emerged is considerably different from the interpretative community the Reader belongs to. Let me add that, according to Potebnja, no meaning can be generated outside a particular time and place, [Fizer 3] that is, outside a particular interpretative community. “External forms that are either ‘ahead of time’ or ‘behind time’ rather than ‘in time’ are, in Potebnja’s view, hardly aesthetically significant” [Fizer 39]. According to Fizer, this is the point, in fact, where Potebnja and other scholars referring to an ‘internal form’ or ‘representation’ [Croce, Vossler, Spitzer] have opposite views [2–3].)

Layer II can be defined as the structures generated by the text in the Reader during the act of reading. Theoretically, it contains all possible structures; it is during interpretation (generation of layer III) that the Reader emphasizes certain structures and suppresses others. As a psychological detour, let me point out that this framework requires the generation of neither layer II nor layer III during reading to be conscious processes. It postulates, moreover, that the conscious and verbalised version of the Reader’s interpretation is necessarily simplified and abstracted (see theme).

Layer II, therefore, has a dual nature. On the one hand, strictly speaking, it exists only in the Reader and is a result of reading; on the other, during its generation, in theory, no inter-Reader differences have yet been introduced. It is supposed, in other words, that layer II is identical across readers.

In Potebnja’s theory, similar three layers can be found: the external form (layer I), the internal form (layer II) and signification, content or idea (layer III) (Fizer 23, 37). His views agree mine in suggesting that signification “changes markedly in every new perception” (qtd. in Fizer 23); in that the internal form tends to expire, reducing the structure of literary (Potebnja talks of poetic) works “to two constituents—external form and signification—and its potential polysemy to a referential monosemy” (Fizer 27, see also 33); and in that one of the main differences between poetic and non-poetic (scientific, in the extreme) texts is that the latter lack internal form (Fizer 36). Despite these similarities, there are also a number of differences between my framework and Potebnja’s theory. In his view, the poetic work contains its internal form (Fizer 23), which, like the external one, is internalised in the act of reading (Fizer 28). Fizer even suggests that Potebnja treats these two forms as “linguistic givens” (47). Opposed to this view, I hold that it is only the external form (layer I) that is transmitted and internalised in the strict sense. While the ‘quasi-objectivity’ of layer II might tempt one to regard it as coded into the text, I would argue against such view partly because it has the danger of simplifying the investigation of the internal form (layer II) to linguistic categories. Nevertheless, I shall also, at many instances, group layers I and II and oppose them to layer III in my proceedings.

The linguistically coded nature of layer II in Potebnja’s theory possibly makes more sense if one considers his suggestion that the word has a threefold structure similar (in fact, identical) to that of literary texts (Fizer passim, esp. 37)—a notion entirely missing from the framework I am presenting.

Similarly to Potebnja, I regard one of the central structural building-block of layer II the image. In the present framework, it functions as a sample structure with which it is attempted to analyse and describe the structures on layer II. Potebnja goes as far as equating image with the internal form (layer II) (Fizer 40). Describing the threefold structure of the word and the work, however,

[w]hile it was relatively simple to define the internal form of the word, inasmuch as Potebnja equated it with its etymon, the image of the work of poetic art eluded an easy definition. His theory, in spite of the central importance of internal form, gave no definition of the image. (Fizer 40–41)

My definition of the image is relatively simple and flexible. It is a set of related elements,[6] with a special element, the imaged at its centre, which is described and enriched by the others related to it.

This framework goes further, however, in forcing a prescribed structural set-up on layer II. It postulates that images themselves are ordered hierarchically. Images at the centres of these hierarchies are the base images. Sometimes it is possible to select one base image for a whole work. As it is assumed that the experience is represented, or ‘expressed,’ by layers II & I, base images can be associated with portions of this experience, or, in the case of one central base image, the experience itself. In the latter case, the imaged of this one base image is regarded as the imaged of the literary work.

Potebnja’s ‘main image’ might be related to my ‘base image,’ however, as the following excerpts show, main image, for Potebnja, is an idea that precedes the work, or a complex which consists of subordinate images.

A complex artistic work is exactly the same kind of development of the main image as the complex sentence is the development of one emotional image (qtd. in Fizer 45)

Individual images, in order to yield content, are to be arranged in some relation of subordination and interdependence. The main image is either a complex that consists of subordinates or an idea of the intended object, graspable in the sensibly perceptible form. (Fizer 45)

While I agree with Potebnja that inter-image relations are necessary, in my framework, the base image is an image on its own, which is merely related to other images. It is not lifted out of the hierarchy and out of layer II, as an emotional image is lifted out of a sentence or an idea of an object from the set of images. In my framework, the base image is homogeneous with the rest of the images.

It is also worth noting that while Potebnja himself did not define image, Fizer attempted to abstract a definition from his arguments. According to him, Potebnja regarded the construction of images as happening either step by step, combining representations in words (a mode, according to Potebnja, preferred by narrative) or suddenly, at certain points in the text, where the internal form of a word dominates those around it (a mode preferred by lyrical texts) (Fizer 48). My definition of the image appears to be a combination of these two modes inasmuch as every image is postulated to have a centre while is enriched by a series of other elements at the same time.

I define the theme of a work of art as its experience or interpretation abstracted to a level which is common to all interpretations and the experience. (In this framework it is supposed that it is possible to do so based on the similarity of Readers in an interpretative group. However, in a less simplistic model of composition and reception of artistic works this postulate clearly should be refined or done away with. For the sake of the present argument, however, let me suppose that generally it is possible to determine the theme of certain works. ‘Theme’ is also used sometimes synonymously with ‘the central problem in the experience.’) Metathesis refers to the relationship between the represented theme / experience / interpretation on layer III and the representer layers II & I. In other words, it relates the experience centred around the theme and representations centred around the imaged of a work. If there is no metathesis in a work, that is, when layer III is directly rendered into layer I, and layer II is missing, the text is considered to become non-artistic, as suggested above.

The lyrical I is the addresser of the embedded communication, the intratextual Author provided the existence of two layers of communicative schemes is postulated (see, however, footnote 4 for a possible extension). What this framework adds to this model is that—pushing its various suggestions to the extreme—it supposes that one of these represents the other. As if building on the problematized status of the Reader in the model of embedded communications, this framework does not consider the possible representation of the Reader in the artwork.

I termed the relationship between the Author and its representation, the lyrical I alienation, mainly because I generally suppose them to be distinct and connected by nothing else than the representational relationship. I regard metathesis and alienation parallel and hardly separable processes, as one describes rendering the object, the other the subject of an experience into the object and the subject of a representation. Thus, alienation, similarly to metathesis, is required for artistic texts, as far as the scope of the present framework reaches. This requirement, let me point out, echoes the notion of the death of the Author as a necessary step (technique) in writing. As it has been suggested, T. S. Eliot and Mark Schorer, among others, refer to the alienation of the experience from the original experiencer, the Author.

Equalling alienation and metathesis has the important consequence that—as far as theme can be regarded ‘objectively’ derivable from a text, and therefore regarded, in a limited sense, intratextual—general Authorial presence, that is, the extent of alienation manifests itself in the internal structure of an artwork, in the extent of metathesis, in the span between theme and imaged.

What this framework provides, therefore, is a model of the representation of the Author and its experience in a work of art, together with a few concepts and suggestions to investigate this representation. These tools will prove useful in the analyses of Browning’s poems, in determining the status of the intratextual and the extratextual Author, and in investigating the ‘deadness’ of the latter in dramatic monologues.

The above concepts also allow a suggestion—based on preliminary analyses of some dramatic monologues—regarding the internal structures of the poems. It is based on the observation that the Speaker appears to be the most central and most thoroughly described element. In this sense, it may well occupy the position of the imaged around which layer II is organised. In other words, the suggestion is that the lyrical I and the imaged are equal in dramatic monologues.

This suggestion clearly differs from Robert Langbaum’s suggestion on the essential nature of dramatic monologues, and even from other descriptions of this ‘genre.’ The differences shall be elaborated and both theories will be tested on specific cases in the coming sections.

Based on the suggestion that the lyrical I and the imaged are representations, however, their equality could be applied to the represented layer, layer III. In other words, my suggestion would entail that the Author is the theme in dramatic monologues. This, inferred proposition shall also be discussed, especially from the point of view of the irrecoverableness of layer III.

Based on my brief review of texts announcing the death of the Author it can, I think, be suggested that the direct application of these theories to literary texts is made problematic by two considerations. First, as Burke’s deconstructionist attempts show, the problematic nature of anti-authorial arguments surface when the status of the their texts is considered. If applied directly to literary texts not addressing the problem of the Author, they appear either to relapse into a prescriptive methodological argument excluding the Author from the scope of analyses, or into an argument which suggests little of the death or the survival of the extratextual Author as it addresses primarily the status of a transcendental entity. Second, many anti-authorial texts appear not to uphold meticulously a distinction between the various types of Authors the existence of which could be considered, required or prohibited in literary discourses.

It was in order to ease the application of such arguments that I made an attempt to separate the functions of the Author in a hierarchy based on a model of communication and restrict the scope of my analyses to a number of these functions. The concepts of the representational framework shall also aid the analyses of literary works by providing tools to describe and trace the relationship between extratextual and intratextual entities.

The analyses of specific literary works in which I investigate to what extent the Author can be or is regarded dead might help, in my view, to determine the scope of applicability of anti-authorial arguments and the possibility of translating them into interpretative or critical strategies.

[1] Throughout the text, I use ‘intratextual’ also in the sense of ‘derived from the text,’ even if the resulting entity is not intratextual in the strict sense.

[2] The model described in this section originates from my idea outlined in an essay written for the seminar Literary Theory ANN-312.22 led by Veronika Ruttkay in the 2004 autumn term at the School of English and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University.

[3] Jakobson refers to A. Marty, who launched the term ‘emotive’; K. Bühler, whose model of language was confined to the addresser, message and addressee, and, accordingly, to the referential, emotive and conative functions; and B. Malinowski, who introduced the term ‘phatic’ (Jakobson 35–37).

[4] If the intratextual Author is to be analysed as different from the Narrator or the Speaker of a literary work, that is, if Derrida’s way of postulating two frames around the narration is to be followed, then the representative relationship occurs between the addressers of the uppermost and the lowermost of the three levels.

[5] The main points of differences, regarding the concepts to be introduced, are: - I have introduced layer III, mainly based on, but slightly altering Potebnja’s theory. Ms Babits only dealt with layer I (the external form) and layer II (the internal form). - Ms Babits introduced the notions of theme, lyrical I, image, base image, element of reality and the imaged. However, they were introduced via exercises only; their formal definitions are in each case my own work. - Ms Babits suggested the notion of metathesis and the investigation of the ‘distance’ between theme and the imaged to capture its effect. In my model, with the introduction of layer III, metathesis is now situated between layer III and layers II & I. I have introduced the notion of alienation, and suggested that alienation and metathesis are essentially the same processes.

[6] By ‘element’ I mean a lexeme or simple phrase usually capable of evoking visual associations; most often nouns or short noun phrases. The category, however, can be widened to include various content words.